THE MAKING OF THIS BOOK

HOW IT ALL BEGAN

I fell in love with photography as a child, when I learned to play with cameras during my father’s archeological expeditions. That passion carried through into my professional life, and in 2006 I published Unseen Lithuania, my first photography book. In two years it became a bestseller in my country, inspiring me to continue my work as an author and photographer; two years later I published Heavenly Belize. After it also became a bestseller in its home country, I decided to take on the largest and most challenging (if not entirely impossible) project of my career. Thus the idea of Unseen Cuba was born.

I arrived in Cuba for the first time in 2010. As I was showing copies of my published work to local officials, I noticed how they admired the photos. Nevertheless, no one believed that it would be possible to produce such a book about this country.

For the raw idea to come to maturity, I have to thank and give great credit to Sergio Gonzáles, who at the time was the Cuban ambassador to Finland, Latvia and Estonia. Sergio believed in the project, and his confidence spurred me on and helped me through many difficult moments. He visited my exhibition of Cuban photographers in Vilnius, and we soon became friends. The greatest surprise was that his brother, Roberto, would later become my pilot. It was a wonderful coincidence. I hardly imagine there exists anyone else in the world who knows Cuba better than Roberto and I. Together we have canvassed this country from one end to the other.

“CUBA LIBRE” AND THE RULES

One of the most famous cocktails in the world is the Cuba Libre (“Free Cuba”), a mix of Cuban rum and American Coca-Cola. For me, the name took on a paradoxical quality; I could not have imagined just how challenging this project was going to be, or how far from “libre” I would be to achieve my goals.

If I were asked today to undertake another photography project in this incredible country, I’d have to consider it very carefully, because there are no clear rules in Cuba. And many times when you find ways to overcome the obstacles in your path, you can’t even explain how you did it.

When I first began this undertaking, I naively thought that, as an impartial foreigner, I would be able to secure the needed permissions to take aerial photos of the country without too many complications or setbacks. And before traveling to Cuba, I consulted with people who knew the country better than I. One of them, the Lithuanian journalist Algimantas Čekuolis, remarked that in Cuba, “Rum is plenty, but what is lacking is freedom by a huge margin.” In addition, two Lithuanian businessmen who had been looking to start a tobacco trade with the country warned me that projects move slowly and agreements are forgotten easily. I soon learned what they meant.

This creation of this book involved navigating the turbulent waters of local bureaucracy and slicing through a near-inexhaustible supply of red tape. After nearly five years, it has levied a hefty tribute of time, money and nerves. “We do everything seriously and methodically,” a Cuban official once told me. That proved only too true!

THE FIRST FORAY

For my first visit to Havana in 2010, I have to thank Irina Cascaret, a travel agent, translator and coordinator who organizes guided tours to Cuba for Lithuanian businessmen and tourists. At first I was surprised by her Russian name, but later I learned that there are many Vladimirs, Ilyichs and Vostoks in Cuba.

Irina’s help could not change the rules by which this country operates. On that first trip, I arranged business visits with ministries, artist and photographers associations, the Council of Heritage and similar institutions. And at first, it seemed that everything was going smoothly and successfully. I was kindly welcomed and attentively heard. Many officials even nodded approvingly at everything I said.

With Pedro Monzón Barata at the Ministry of Culture, after signing an agreement on June 21, 2010. According to the contract, the Ministry agreed to supervise my project

I had brought copies of my other photography books with me, and my Cuban contacts were fascinated with my recently published work, Unseen Belize. They enthusiastically congratulated me on my work and expressed their profound interest in Cuba being the subject of my next book. I was confident that their interest was genuine and honest. As I never asked for any money and promised that my publishing company, Unseen Pictures, would finance the entire project, I had high hopes for success. However, although my work was well received for its artistic value and quality, I could see that the locals felt it would be a miracle if someone (it did not matter whether they were Cuban or foreign) received permission to fly over the country to take pictures.

The people I met promised to send me the required instructions to get permission to take aerial photos of Cuba. For more than four years, these instructions never came. “No project can be started without the knowledge of the highest authorities in Cuba,” one of these officials mysteriously whispered. This must have been true: wherever I went, everybody seemed to be waiting for permission from a mysterious higher power

A TEST OF PATIENCE

The misunderstandings and obstacles began early on in the project. I learned that, in order to be authorized to take pictures of Cuba, it was necessary for me to have a work visa and not a simple tourist card. Moreover, even with a work visa I still needed to secure permission from the Cuban Air Force to take off… and no such access had ever before been granted to a foreign citizen.

My endless meetings proved so fruitless that I switched tack and applied to Gaviota Group, a Cuban army-owned company that manages a network of hotels and arranges air travel for wealthy tourists who want to explore the island’s coastline.

One hour-long flight in a huge Russian Mi-8 helicopter and almost $2,000 USD later, I was rewarded with my first opportunity to take aerial pictures of Havana’s coastline (a flight over the city itself was out of the question!). I didn’t use any of those pictures for my book, due to the poor morning light, but the experience taught me that my Cuba project would cost me more than a bar of gold if I paid this much for every hour of flying time. I realized that I would have to resort to other methods and find new ways to overcome these difficulties.

This was the first of many tests that Cuba had in store for me. In retrospect, I can see that this project, and this country, have made me a more patient man. After I relaxed and started to work within the system, things began to progress much more smoothly.

CHE GUEVARA WAS A PHOTOGRAPHER TOO

As part of my efforts to gain greater visibility for my project, I organized a seminar for Cuban photographers in May 2010. It proved to be a good idea; the local press, artists and celebrities were interested in the event. I talked about aerial photography and showcased my books. I was then invited on one of Havana’s radio talk shows for an interview about my plans to take pictures of Cuba from the air.

My books and the project impressed Liliana Núñez Velis, the daughter of Antonio Núñez Jimenes, a famous Cuban scientist and geographer. Her father was an associate of Fidel Castro who, after the revolution, established the Foundation for Nature and Humanity. After his death, his daughter took over as head of the organization.

Liliana invited me over for a chat and told me about her father’s activities, archive of photos, books and archaeological artifacts. I was surprised when she told me that Che Guevara himself was also a photographer. Liliana was very helpful and offered to write a recommendation letter to the Cuban Ministry of Culture, to which her foundation was a subordinate.

Thanks to Liliana, I met with Pedro Monzón Barata, the head of the Foreign Affairs Department at the Cuban Ministry of Culture. I had counted on the Ministry of Tourism’s support for this project, but unexpectedly it was the Ministry of Culture that became more interested in the book. After two months (in Cuba, this is record time), we signed a cooperation agreement. The ministry promised to coordinate the permissions and help organize the logistics of the project, and I pledged to donate 500 copies of the published book. I also promised to let them review all the photos I’d take, strictly follow the flight plan I was granted, and shoot only those areas for which permits were issued.

THE SEARCH FOR WINGS

I began making regular visits to the Ministry of Culture and one of its subsidiaries called Paradiso. This company was responsible for supervising my project and for coordinating any payments I had to make to other Cuban enterprises and organizations.

Now all I needed was to find a flying device that would be acceptable to the Cuban airspace controllers, the military and the civil aviation authorities. While flying and photographing in other countries, I often used ultralight trikes made by Airborne, an Australian company. I decided that the only way to make this project happen was to buy my own ultralight. I placed the order for one to be manufactured and shipped from Australia to Cuba.

Liliana Núñez Velis was instrumental in helping me secure the support of the Ministry of Cultur

Each stage of the project took a long time. Before booking the ultralight, I had to confirm that I would be able to import, register and operate the craft. I also had to find out the technical requirements of the Civil Aviation Institute. These procedures took several months.

BEWARE OF THE NORTHERN NEIGHBOR

While waiting for the technical requirements with which my ultralight had to comply, I created and published a book of aerial photographs of Cancún and the Riviera Maya, the resort region of Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula.

During one of my many meetings, I showed my new book to officials in the Ministry of Culture and allowed myself to joke about how things were going so slow in Cuba that, while waiting merely for a few tech specs, I managed to produce and publish a whole book on a neighboring country. There were some 20 participants in that meeting, and one of them countered: “It is not that we are slow in Cuba. We are very thorough and methodical! We have to make sure you won’t be causing any danger for our country with your flying little trike. One must never forget that the northern neighbor is breathing down our necks!”

The officials wanted to be sure that, while flying over Cuba with my ultralight, I wouldn’t perform any unauthorized activities like distributing leaflets or dropping biological weapons. Their suspicion effectively eliminated all the humor from the proceedings, especially since I had already invested too much time and money, only to have my project still be on hold.

LITHUANIA IN HAVANA

February 16, 2011 marked Lithuania’s Independence Day, and I organized an exhibition of my native country’s photographs in Fototeca de Cuba, Havana’s photography museum. I invited close to 200 influential citizens of the capital and presented Unseen Lithuania and a collection of 40 oversized prints at the event. Some 30 friends of mine from Lithuania came to Cuba for this exhibition. The book made a big impression among the Cuban attendees—it was mentioned in the press, radio, and TV, and Havana’s artist community was talking about it.

The news about my previous work and the possible book of aerial photography on Cuba had started to spread. The PR move worked; after two more months I finally got all the requirements from Cuba’s Civil Aviation Institute about what aircrafts were allowed to fly over the country.

But this wasn’t the last of the bureaucratic obstacles I would have to overcome.

DON’T SEND ANYTHING THROUGH THE US

After receiving the technical requirements, Airborne informed me that I would receive my custom-made ultralight within 35 days. However, it turned out that the shipment could only be made via a direct route to Cuba. It had to be transported without entering any US port, and it also could not be transshipped. Another obstacle occurred when Cuban officials delayed to decide and let me know to which address the ultralight had to be sent.

As I was already familiar with how long decisions take in Cuba, I decided to take a risk and find the receiving party myself. I discovered the company Aviaimport in the Cuban Yellow Pages. It sounded appropriate, so I listed its address as the receiver. And only after the ultralight was on its way from Australia and there was nothing to be changed did I inform the local authorities that an expensive package was coming to the Havana-based Aviaimport. The trick worked, and I finally understood how things function in Cuba: It’s better to act first and then explain… in other words, it’s better to ask forgiveness than permission!

THE MISSING PILOT

It took more than two months for the ultralight to travel from Australia to Cuba. Along the way, some of its cabling and contacts got rusted from humidity and improper storage. And then, after the long trip, the aircraft got stuck in Havana’s customs for another two months. Moreover, I was told that there was no certificated specialist in Cuba who could assemble the ultralight and test-fly it. As far as I understood, there were enough experienced technicians, but under the requirements it had to be a specialist with a certificate to assemble and try out exactly this particular aircraft

I invited Robert Combs, an American pilot with whom I had flown on trips to Hawaii and Belize. It was agreed that before Robert’s arrival, the ultralight would be cleared through customs and taken to the aviation base in the town of Colón, but this did not happen. We successfully authorized Robert as a recognized Cuban civil aviation pilot and instructor, but because of the delay in Cuban customs, Robert could not wait any longer and had to return to Belize. It was a costly setback.

When the ultralight finally cleared customs, Robert disappeared unexpectedly and did not return my calls or emails. I was in trouble on two fronts: my ultralight was unassembled and my certified pilot had vanished. I couldn’t think of any logical explanation to give to Cuban officials about his whereabouts, especially after I had vouched for him. I flew to Belize to search for Robert but he was nowhere to be found.

I returned to Cuba and invented a tale that my pilot had unexpected family problems. Now I needed to find a new pilot; I could have asked Airborne for a specialist, but I didn’t want to take any further risks and work with strangers. I decided instead to ask Lithuanian pilot Artūras Laukys to go with me to Cuba. I had already flown with Artūras over Lithuania in 2007. He was not only a very experienced pilot and instructor but also a very good mechanic. He had designed and built a few ultralights himself, so I had no doubts that even under difficult circumstances, Artūras could help me.

THE FIRST FLIGHT

Artūras and I came to Havana and we got Artūras certified with unexpected speed and efficiency. He became an instructor pilot recognized by the Cuban Civil Aviation and authorized to assemble and test my ultralight. Finally, we were able to set out for Colón, which was about 3 hours from Havana by car.

It was raining all week in Colón. Artūras led a team of mechanics who constructed the ultralight, and we finally started it. But because of the bad weather, we were afraid that our first test flight wouldn’t happen. We stayed in a town called Varadero and drove for 4 hours back and forth every day under the pouring rain in the hopes of conducting our all-important first flight. Cuba suffered heavy flooding that June of 2012, and the sky did not show any chance of clearing. Later I calculated that I flew more than 6,000 miles in Cuba’s airspace, but drove more than 30,000 miles on the island’s roads.

In the end, we successfully assembled the ultralight. Artūras trained our Cuban pilot, Roberto González, on how to control this particular aircraft—Roberto already knew how to pilot a similar type of ultralight. On the day the special commission arrived from Havana with our approval that it was safe to fly, the sky was overcast, but luckily a small break formed in the clouds, and Artūras and Roberto took off at last.

Our radio didn’t work, but the commission still signed the approval that we now had the right to fly, and that the aircraft met all safety requirements. The Airborne XT-912 is a very reliable and quite simple ultralight with a Rotax motor. It can fly for 5-6 hours at approximately 55-60 mph. The pilot sits in the front with the passenger in the back. It’s hard to take pictures because of the wing and cables, but after extensive practice I found a way to do it. I had more than 100 hours of experience with this type of aircraft in Hawaii, Belize, Australia, Lithuania and Italy, among other destinations. In each of these countries, the civil aviation authority treats them as simple experimental aircrafts that are very simple to operate—often it is not even required to have a flight plan, radio or transponder. And usually the owner is both the pilot and mechanic of the ultralight, as its maintenance is almost equal to that of a motorcycle.

Of course, things in Cuba are different. In the eyes of the civil aviation authorities, my ultralight was seen almost as a Boeing – every flight had to be registered, the flight plan had to be filed the day before each flight, and we had to have radar and a transponder. Moreover, aviation inspectors required that the ultralight must be maintained by a separate mechanic (who also had to have the flight plan register), and frequent fuel tests had to be conducted to make sure there was no water in it. That’s how the technician joined our team. His name was Ariel Govin, and he was a friendly, lively and professional person. An additional member of the team meant more expense, but I’ve never had any regrets about Ariel, who was very attentive and also ensured the safety of our flights.

CRAZY PRICES

After the test flight In June 2012, it seemed that we would be able fly over the whole island. Unfortunately, we were mired in negotiations with ENSA, the National Air Services Provider for Cuba. We reached an agreement with ENSA that allowed me to operate my ultralight using their resources and infrastructure for the duration of the project. They also gave me a pilot, mechanics, runways, and any required maintenance and servicing. However, they wanted to charge an exorbitant and unacceptable price for their services, regardless of whether I was in Cuba or not.

Due to my other business projects and my family, I usually travel for about two weeks before returning to Lithuania. If I could have stayed in Cuba for a half year, maybe I would have been able to accept the ENSA’s proposed prices. Unfortunately I knew that I would have to come and go from Cuba at least for a couple of years. Also I wanted to capture the island at different times of the year. Besides, I knew from experience that sometimes it takes weeks to wait for the perfect weather for flying and taking photos. So, I had to find the best financial solution for these working conditions.

While in negotiations with ENSA, all certificates and permissions were canceled, and I had to go back to the ministries. I was required to insure my ultralight for the entire year and not for the duration of my work. The national insurance company asked for a payment that was almost one third of the cost of the ultralight. They only lowered the price after I showed them how much the insurance for the craft cost in European countries and the US.

During the two years of flights, Ariel and Roberto became true members of my family.

In the end we came to terms with ENSA, and it looked like there were no more setbacks… but they seemed to appear all the time out of nowhere! For example, after a two-month break I found out that ENSA had undergone a restructuring and was now reporting to a higher body. The new management decided to evaluate my project again. A new committee was formed to verify the suitability of the ultralight, and an inspector was dispatched to reevaluate the competence of my pilot and technician.

BREAKING THE ICE

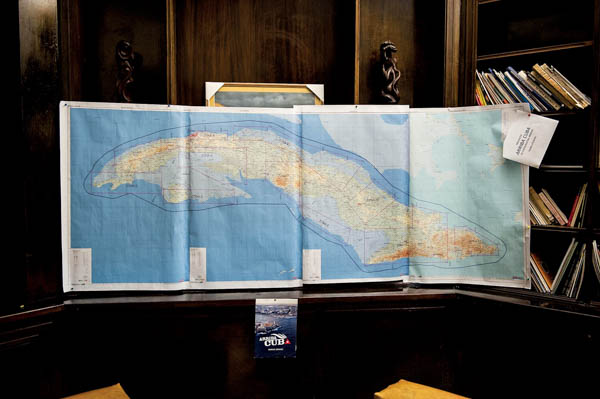

In the beginning of the project, when I signed the cooperation agreement with the Ministry of Culture, I was given a map that specified where I was allowed to fly and take pictures. I had to adhere strictly to this map without flying anywhere else. Unfortunately, none of Cuba’s cities were included in the map, despite the fact that anyone could see these areas in detail simply by using Google Earth.

It was difficult to imagine the book without any pictures of Cuba’s main cities. Fortunately, I had by now understood that some forbidden actions could be carried out, as long as they were done quietly and only after you waited patiently for your chance. Romper el hielo is a Cuban expression that means, “to break the ice.” If you’re able to do something once, the next time the same task may require less effort and will be easier to carry out.

I managed to take pictures of cities like Holguín because we had to pass through part of the city while taking off, thanks to wind direction and the city’s proximity to the airport. It was an innocent excuse, but sometimes I would tell the Air Traffic Control Center that I was a distracted foreigner who forgot the right camera lens, so we had to land and take off again.

I decided to arrange a small presentation to Ministry of Culture officials and show them how my work was progressing and what the book was going to look like. I included pictures of some of the bigger cities and asked them to consider my request again and Roberto Gonzalez is probably the best pilot I have ever flown with.allow me to fly over

Santiago, Camagüey, and especially Havana. I think I convinced them that the photographs were merely artistic and did not include any forbidden objects, because eventually I received permission to photograph most of Cuba’s cities.

Unfortunately, Havana remained off limits. I was told that flying over the capital was strictly forbidden, and no miracle would change that rule. However, after a few more months, in April 2014, I was allowed to take pictures of Havana as well. For the first time, I could envision the end of the project. A special route was created which indicated where we could fly over the capital. The pilot had to report every three minutes on what building we were flying over. Moreover, Roberto was summoned to the air force base and specially trained in what directions and height he could fly in, and what was forbidden. I had finally broken the ice, and there were no further obstacles standing in the way of the project.

Toward the end of the project I discovered that ENSA was not paid by Paradiso, the company through which I paid all service providers in Cuba. Employees of the company explained that they had run out of money, even though I had transferred a larger amount than was agreed upon.

Unpredicted obstacles were really frustrating, and moreover were stopping the work. Once I even threatened to list the names of all those who impeded my work and negligently performed their duties in the book. After that, the requisite funds appeared immediately and were transferred to ENSA so I could continue my flights.

When I took my kids with me to Cuba, they quickly became good friends with Roberto and Ariel, and often would befriend local children.

THREE REMAINING PHOTOS

Even though it looks small on the map, Cuba is a big, long country that spans more than 700 miles from end to end. My style of photography requires mild, yellowish or reddish early morning or late evening light that can be found in Cuba’s latitudes about one hour after sunrise and hour before sunset. Later, the sun is too high, too harsh, the shadows disappear, and everything looks like a map or an image from Google Earth. In my opinion, such images have little artistic value and are more a type of technical illustration. That’s why the photo shoots took almost two years to complete.

We started to photograph over Varadero, and later traveled over the northern coast until we reached Baracoa. From there we traveled to Guantánamo before continuing along the road back to Havana. At every spot, we stayed in private houses (casa particular), where we spent anywhere from a couple of nights to a couple of weeks. Everything was controlled by nature and by the “gods of Cuban aviation.”

We reached Havana at last in April 2014. I has already secured the permissions to shoot over the capital and had four days to take marvelous pictures with both morning and evening light. From Havana we flew to Pinar del Río, where we had to photograph the Viñales Valley in the western part of Cuba to complete our shooting.

Unfortunately, we ran into an unexpected problem. When everything was almost done and only three photos were missing, the weather took a turn for the worse, with strong winds and pouring rain. It was very difficult to cope with the idea that I would have to go back home and then come back again just for those three pictures, but I couldn’t produce the book without Cuba’s magnificent Viñales Valley, a UNSECO World Heritage Site. In spite of the bad weather we tried to fly, but only ended up taking a big risk in vain.

The morning before our departure to the airport, officials from the Ministry of Internal Affairs arrived. Apparently some of their offices were not aware of the shooting and had received reports about a possible foreign spy who captured Cuba from the air. My pilot and I were taken in for interrogation.

I was questioned nicely but very slyly. One officer told me he was interested in photography and asked how it was possible to transfer the pictures from my modern camera to a mobile phone, how many times the image can be zoomed in, and whether it was possible to take pictures in the dark, among other questions.

By a stroke of ill luck, I had forgotten my passport at home. When I told the officials that I could come back with it immediately, they did not allow me to do so and said that they would find the document on their own. Finally my interrogators left after writing a protocol of interrogation. However, when I returned to Cuba after two months, I found out that legends were being whispered around about a foreigner who, with the help of two Cubans, was flying illegally. The officers had allegedly caught him dismantling the aircraft and trying to flee the country. The story sounds funny now, but at the time it brought a lot of unnecessary mess to the already chaotic process of issuing permits to fly.

After a two-month break, we took off and started to fly over Viñales to get my last photos, only to be ordered to land immediately. Because of the story circulating about me and my project, someone had decided to reexamine the legality of my project. We had to wait two hours for a permit to fly.

The weather in June 2014 was favorable and I secured my remaining pictures. The photographic part of the project was now complete, and I began the process of editing, designing and writing the book, and preparing it for printing.

THE ROLE OF A SINGLE DAD

This journey became very precious to me because I had more opportunities to be alone with my children. I learned how to be a single dad. Being away for more than a week without my family was always a burden for me. That’s why I try to take them with me wherever I go, but it’s not always possible. Once I had to spend three weeks in Cuba, and I took my five-year-old son, Vincent, so I would not long for home.

A fair-haired blond boy, Vincent has become a star in Cuba. Cubans love children very much and most of them are very dedicated to their families. Ariel immediately developed a strong bond with Vincent and became a very good nanny. My son had to get up at 5 o’clock in the morning and go with us to the runway. While Roberto and I were flying, Vincent stayed with Ariel on the ground. After we completed our work in one destination, we flew to another one, with Ariel and Vincent packing our baggage and following us by car.

I taught Vincent to say a few useful phrases in Spanish, like tengo hambre (“I’m hungry”) and tengo sueño (“I’m sleepy”). He soon learned to count and identify colors in Spanish. Ariel also had to learn some Lithuanian to understand when a child wants to stop and go to the bathroom or to call dad.

Ariel and Roberto were a great help in taking care of my children, Vincent and Maria Isabel. They are experts at entertaining kids and playing with them!

It was wonderful: I would fly in the early morning and late evening, but during the day I’d spend time with my son, playing football, teaching him to read and count. Ariel taught him to play baseball and Roberto played UNO with him.

On one trip I took both Vincent and my ten-year-old daughter Maria Isabel. Our family is used to traveling with children. We always travel with my wife Brigita, but this time she stayed in Lithuania with our one-year-old baby Antanas.

It’s not difficult at all to travel with two children in Cuba. They played together and of course made friends with Ariel and Roberto immediately. Unfortunately, Maria got food poisoning with coconut water. She was sick for days and had to be treated at the children’s hospital in Santiago de Cuba. The Cuban doctors who diagnosed her were real professionals, and within three hours she was feeling better.

The weeks I spent with my children in Cuba will remain as some of the most precious memories of my lifetime.

ABOUT THE EQUIPMENT

After every flight, I transferred RAW format pictures to an Apple MacBook Pro computer. For the selection I used Adobe Lightroom. I collected a total of 50,000 shots. Because of the constant shaking of the ultralight, it proved nearly impossible to shoot high-quality video. While photographing in Lithuania, I found a way to shoot 1-2 frames per second, which I later converted into a stabilized video. I did the same with Cuba’s photo material. Examples can be found on YouTube and by downloading Unseen Cuba from Apple iTunes and other online stores.

All the pictures were taken while flying in an Australian ultralight “Airborne XT-912” with Cruize type wing. The ultralight was new, custom-made for this project, and equipped with radio communication, transponder and even a spare parachute in case of emergency. The average flying height was about 300 feet. Our top height was 1.2 miles, which we reached while flying over Cuba’s highest peak, Pico Turquino, in southeastern Cuba. On average, each flight took 1-1½ hours.

Low light pictures were taken from the roof of the Capitolio (it took three months to get permission to take pictures from there) and one of the highest structures in Havana: the Focsa Building.

ENSA’s team was very professional. Ariel carefully maintained and prepared the ultralight for every flight. Roberto is one of the best pilots I have ever flown with. Even though we followed the operations manual and flew only in good weather, there were times when we had to experience surprises, air holes, turbulence, sudden winds, and a change in the clouds. However, with Roberto at the helm I felt safe and never worried that the shoot would be compromised. All in all, two years of working together made us like a family.

FITNESS AND A HEALTHY LIFESTYLE

I’m an avid triathlete and enjoy leading an active lifestyle. When the mornings were cloudy, rainy or otherwise unsuitable for flying, I would spend my time running or cycling. If we would fly out in the morning, upon landing I would change into a sport suit and spend my time running home or discovering a new route. Sometimes I had to train in the hot, midday Cuban sun, but it helped me to adapt to triathlons in hot climates.

I brought my bike to Cuba. Ariel used it while I wasn’t there, and Roberto also began jogging or hiking a little bit. This is how I included my team in sports activities, encouraged them to eat more vegetables, and not take sugar with their coffee. I’m a vegan, so while traveling I also try to promote healthy nutrition and lifestyle.

While in Cuba, I ran my first ultra marathon of 33 miles through the mountainous “La Farola” road that Running under the hot Cuban sun helped me prepare for triathlons in hot climates.stretches from the Atlantic Ocean to the Caribbean Sea and connects Baracoa with the southern coast of the country. Roberto and Ariel helped me a lot. They accompanied me by car with a trunk loaded with coconuts, bananas and sweet potatoes. I also managed to do an olympic distance triathlon between Trinidad and Cienfuegos. On another occasion, we organized a half Ironman triathlon from Varadero to Havana. It included 1.2m of swimming, 56m of cycling and 13m of running.

All in all, I ran some 620 miles and cycled more than 1,240 miles. Since we weren’t usually stationed by the sea, I didn’t have many opportunities to swim. Instead, I brought my strength exercise equipment to Cuba: resistance bands, belts and dumbbells that I bought in Havana. Often while waiting for my team to prepare the flight, I would unroll the yoga mat and do flexibility exercises

Not only did my exercises allow me to spend my time between governmental meetings more constructively, but they also increased my fitness to quite a high degree. After my last trip to Cuba I competed in and finished my first Ironman Ultra Triathlon in July 2014!